A long-term relationship between purchaser and supplier is necessary for best economy.

—W. Edwards Deming

Supplier

A Supplier is an internal or external organization that develops and delivers components, subsystems, or services that help Solution Trains and Agile Release Trains provide Solutions to their Customers.Lean-Agile Enterprises deliver value to their Customers in the shortest possible lead time, with the highest possible quality. Suppliers support this mission by providing unique competencies and distinctive skills and Solutions. They provide unique expertise that can accelerate and reduce the costs of solution delivery. Many Solution Trains and Agile Release Trains (ARTs) depend on supplier performance for their overall value delivery.

Suppliers will use varying development and delivery methods. Nonetheless, the SAFe Enterprise treats suppliers as long-term business partners, involving them deeply in the solution. They also work with suppliers to actively help them adopt Lean-Agile Mindsets and practices to increase the economic benefit for both parties.

Details

Suppliers play a critical role in SAFe. They provide unique expertise and/or components and subsystems that accelerate solution delivery. Suppliers can have a considerable impact on the entire Development Value Stream’s goal of delivering value to customers in the shortest sustainable lead time.

Some suppliers are external to the enterprise. Others may reside within the organization and are often producing products as part of another SAFe Portfolio (e.g., business unit). In either case, suppliers typically have their own independent mission and solutions to deliver to other clients, as well as their own Economic Framework to drive decisions. For both organizations to achieve optimal results, close collaboration and trust are required.

Changing the Supplier Relationships

Many organizations delegate supplier selection and contracting to a separate procurement organization. This can lead to an emphasis on near term pricing without a complete understanding of the overall value and longer term economics. There are other anti-patterns as well:

- In the name of competition, organizations may switch suppliers searching for the lowest price and resource suppliers across the globe in the most economical cost venue.

- Suppliers are typically told what to build through detailed specifications instead of being asked what value can your solutions offer, which doesn’t leverage supplier innovations.

- Organizations magnify this problem by isolating suppliers and only provide information on a need-to-know basis.

- Finally, contract structures can limit a supplier’s ability to adapt, committing them early to a set of predetermined goals.

The Lean-Agile enterprise takes a different view, one that maintains a longer-term, economic perspective via a collaborative, ongoing, and trusted relationship with suppliers. They become an extension of the culture and ethos of the enterprise; they are treated as true partners. Their capabilities, policies, and economics are surfaced and understood. Strategic suppliers are selected based on their alignment in multiple dimensions:

- The right technical and business model fit with the overall solution

- A development model consistent with the buyer’s way of working

- Culture which is aligned with the buyer’s purpose, both now and in the future

However, reaching this state can be a challenge if the supplier’s basic mindset, philosophy, and development approach are materially different from that of the buyer. There are two cases to be considered: one in which the supplier has already embraced and adopted Lean-Agile development, and one where the supplier operates in the traditional waterfall model. Typically, the larger enterprise must address both, but the goal is the same—a more cooperative, long-term, adaptive, and transparent partnership. Each of these models is described in the sections that follow.

Working with Lean-Agile Suppliers

Involving Lean-Agile suppliers is the easier case. The working models and expectations are largely the same, and many current Lean-Agile practices can be simply assumed and extended:

- The supplier is treated like an Agile Release Train (ART) and works in the same cadence as the other ARTs

- The supplier participates in the Program Increment (PI) Planning and Pre- and Post-PI Planning events, where they present what they plan to deliver in the next Program Increment, along with an indication of what will be delivered in each Iteration

- Their dependencies with other ARTs appear on the solution planning board.

- The supplier demos their subsystem or components in the System Demo, participates in the Solution Demo, and continually integrates their work with the rest of the development value stream, providing feedback to other trains

- The supplier participates in Inspect and Adapt (I&A), both to improve the development value stream as a whole and to help improve their Lean-Agile practices

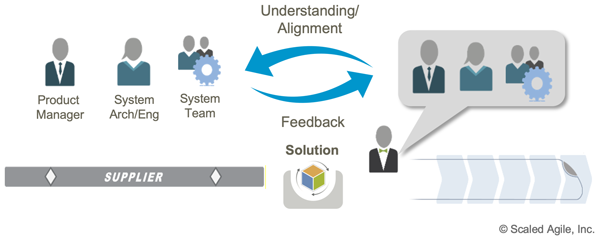

Suppliers continually align with their customers along three critical dimensions (Figure 1). Product Management ensures the Backlog and Roadmap align with the larger solution. Architects ensure technical alignment. And the System Teams share build, integration, and test infrastructure including scripts, environments, and hardware. Ensuring suppliers have a rich, realistic context for testing their components can dramatically reduce delays.

Working with Suppliers Using Traditional Methodologies

Working with suppliers that use more traditional methods is often required. Independent of the method, the value of continuous collaboration across organizations will weigh heavily in the selection process. The more strategic the relationship, the more the organizational alignment becomes critical to overall success. Due to differences in working models (ex., up-front design, larger batch size, and non-incremental development), the enterprise may need to make adjustments:

- The supplier may expect more formal requirements and specifications. Therefore, some early, up-front design time will be needed in the early PIs to allow suppliers to build their plans and to establish Milestones for the supplier to demo or deliver against.

- The supplier may not be able to deliver incrementally; frequent integration may be challenging.

- Changes to requirements and designs need to be understood earlier, and the response time to changes will take more time.

However, some expectations and behaviors can and should be imposed on these suppliers:

- In the pre-PI planning event, they should brief their progress towards upcoming milestones.

- In the solution demo, they should present their accomplishments and provide feedback on the demos of the other trains.

- Involvement in the I&A workshop is crucial since traditional suppliers will have longer learning cycles. They should use this opportunity to raise any problems or issues and participate in the overall solution.

In addition, suppliers may have limited flexibility in adjusting their plans, and, as a result, other trains will have to be flexible and adjust accordingly.

In addition, the solution’s architecture may play a significant role in supplier collaboration. The article Technical Strategies for Agile and Waterfall Interoperability at Scale discusses several technical practices that enable better collaboration with traditional suppliers.

Applying Systems Thinking and Decentralizing Decision-Making

To optimize the flow of value as a whole, it’s important to apply systems thinking at all levels of decision-making about how and how much to involve suppliers. The cadence of integration with the supplier, for example, is impacted by their method of work and also by the transaction cost of the integration. Likewise, how far decisions can be decentralized to suppliers depends on Solution Context. For example, if the supplier is creating a subsystem that interfaces with the solution through well-established standards, it’s easier to let them take more control. But if it’s a proprietary interface that impacts other suppliers, and thus has economies of scale, more negotiation is required. Also, in a highly changing environment, constant collaboration and integration are more important than they are in more static environments.

Collaborating with Suppliers

Collaboration with suppliers occurs at all levels of SAFe, including Strategic Themes. As described in [1], Honda collaborates with its suppliers on the kinds of products and types of markets it plans to pursue in the coming years. This creates better alignment and enables their supplier to offer better value through more strategic offerings. Instead of hiding information from suppliers, Honda shares it for better economic outcomes.

Suppliers also collaborate in building the requirements, avoiding over-specification that can inhibit decentralized decisions and handcuff supplier innovations. Instead of handing suppliers detailed specifications, they are included in the specification process. And during implementation, they strive to keep options open and explore alternatives by using Set-Based Design.

Solution Management works with suppliers continuously and collaboratively to write capabilities and then decompose them into Features. Solution Architect/Engineering works with their supplier counterparts to design the solution. The collaboration cascades to the Agile Teams developing the actual solution. Supplier engineers and their counterparts in the Solution Train communicate directly to collaborate on the best design. The supplier’s teams should be treated as an extension of the Solution Train’s teams.

To enable early integration and improve quality, suppliers and ARTs need to share interfaces, tests, simulators, and other infrastructure. All such interfaces should be documented in Solution Intent so that the information is available to everyone.

Selecting Suppliers

As solutions get more complex, there is a general market shift away from suppliers that create individual parts and components and toward suppliers that provide higher-value, integrated solutions. Even in industries where suppliers provide work for hire, there is a shift from hiring individuals to sourcing whole Agile teams, and even to sourcing entire ARTs.

This trend makes selecting the right suppliers critical since the choice determines a long-term, high-value relationship. To make the best choice, multiple participants from engineering, procurement, and possibly other parts of the business contribute to supplier selection. Since the Lean-Agile enterprise will generally seek fewer suppliers (but enduring relationships with each), these perspectives can better determine the long-term culture, technical, and process fit of the two organizations.

Helping Suppliers Improve

It’s easier and more productive to work with Lean-Agile suppliers; they better align with the cadence and culture of the enterprise and adapt their plans as needed. But in any case, trying to improve the whole value stream without improving the supply chain is not optimal. To address this concern, Lean-Agile enterprises include suppliers in their continuous improvement objectives, to the benefit of both companies.

Inviting suppliers to join I&A workshops and other relentless improvement activities, as well as sending engineers who are proficient in Lean and Agile to help suppliers improve their processes, can have a major impact on lead times and costs.

Agile Contracts

To facilitate effective working relationships with suppliers, it’s important to build an environment of trust between the parties. Traditional contracts can lead to undesirable results and unintended consequences. For example, a cost-plus contract award might yield a competitive, low-cost bid. But the overall cost increases (sometimes dramatically) as changes occur. Such contracts do not optimize the economic benefit for either party.

In its place, Lean-Agile buyers and suppliers collaborate and embrace change, to the benefit of both parties. These relationships are built on trust. Increasingly, these relationships can be built via Agile Contracts, which provide a better way of working [2].

Learn More

[1] Liker, Jeffrey, and Thomas Y. Choi. Building Deep Supplier Relationships. Harvard Business Review, December 2004. [2] Aoki, Katsuki, and Thomas Taro Lennerfors. New, Improved Keiretsu. Harvard Business Review, September 2013. [3] Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis. MIT Center for Advanced Educational Services, 1982. [4] Toyota Supplier CSR Guidelines. 2012.

Last update: 10 February 2021